István Józsa

JÁNOS ARANY’S POEM IN WALES

Interview with Twm Morys, poet, translator and Dr. Heini Gruffudd,

lecturer at the Department of Adult Continuing Education in Swansea University, Wales, United Kingdom

1

-- The poem by Arany János has at last become well-known in Wales in 2012 -- says Dr. Heini Gruffudd. -- It has been translated by a Welsh poet – Twm Morys, and music has been composed especially for the poem by one of our most prominent musicians – Karl Jenkins. This was performed this year in our national festival – the National Eisteddfod of Wales. A CD of the music has been produced by CMI records. The first live recording of the Hungarian language poem set to this music was on 29 June 2012 at the Bartok Bela National Concert Hall in Budapest. The first Welsh language performance was then given in August at the National Eisteddfod.

─ Mr. Twm Morys, have you travelled in Central Europe?

─ I was in Romania not long after the revolution and the downfall of Ceausescu. I was given a Romanian-English phrase-book by a taxi driver in exchange for a Leonard Cohen tape. I’ve been in the Czech Republic and in Slovenia. And I’ve been twice to Hungary.

─ Do you know these countries, in brief, in principles their history, their art, their literature?

─ I know little about them. We learn nothing about them in school. I know more now about Hungary, because of my involvement with A Walesi Bardok! I’ve visited Hungary twice to learn more about Arany and the poem, and I’ve become interested in Hungarian literature in general, and poetry in particular.

─ How many languages do you speak?

─ I speak Welsh, English, Breton, French, some German.

─ From which languages have you translated?

─ I’ve translated from time to time from Breton, French and German into Welsh; from Welsh into Breton and English and French.

─ What about the first contacts with the Hungarian culture? The very beginnings please.

─ My very first contact with Hungarian culture was in Freiburg in Germany, where I lived for a while around the beginning of the 80s busking with a harp on the street. We buskers used to hang out together, and had a merry time of it. One evening, a man dressed all in some furry animal skin, looking like a bear, joined us. He said he was from Hungary, and that he was a shaman. Who was I to doubt him? He sang in a guttural, growling voice, and his company was very welcome. After that, and until very recently, contact with Hungary has only been through Hungarians visiting Wales, and quoting from A Walesi Bardok.

─ Hungarian is one of the most difficult languages in the world - what was your motivation to translate?

─ Welsh is also one of the most difficult languages in the world! But even children speak it... I was commissioned (mostly at the instigation of LASZLO IRINYI) to translate A Walesi Bardok into Welsh as part of a plan to have Karl Jenkin’s musical setting available in three languages: Hungarian first, so that the work written in Hungarian can be performed to Hungarians in Hungarian; English, so that it can be performed in America (and Australia and England); and Welsh, the language of the Bardok! The idea here in Wales was that it could be performed billingually: King Edward singing in English, the Bards in Welsh. This would reflect very well the political situation in Wales then and now, and would give the work a significance quite independent of the allegory Arany intended!

─ When you begin to translate, are you searching for a larger literary, artistic, historical etc. context beforehand?

─ In general, yes. But in this instance, the commission was very specific: to translate the Hungarian text as closely as possible, and in the very same poetical metre, so it would fit the musical score exactly.

─ I think, we should speak here about the possibilities of a United Europe.

─ OK.

─ In your opinion, how should we evaluate the Welsh-Hungarian relationship?

─ As one which has in recent times been entirely on the Hungarian side. Because of Arany’s poem, the Hungarians know more about Welsh history than many Welsh people. The Welsh people, in general, know nothing about Hungary except goulash. But at the time of the 1848 revolution, the Welsh people were very aware of what was happening, and were inspired by the Hungarians’ stand, mostly because of the writing of GWILYM HIRAETHOG (google the name!) in the Welsh- language press. Kossuth himself, when he came to Great Britain, went to see Gwilym Hiraethog in order to shake his hand.

Lately, though, and mostly because of the enthusiasm of LASZLO IRINYI, there has been a new interest. Laszlo came to Wales last year, with a little commando-like force of Hungarians, to the National Eisteddfod (google), where A Walesi Bardok was performed in Welsh for the first time in the world. They set up a kind of a Hungarian Embassy there under canvas for a week. Who knows what might come of it?

─ When we speak about Hungarian culture, we have to speak about six countries. Is this well known in Wales?

─ This is not known at all in Wales! But then, is it known in Hungary that

the oldest Welsh poetry comes from Scotland in the 6th century? That the common people of Wales in the 19 century were the most literate in Europe? That even today there are more poets in Wales than in any other European country? No.

─ Please, tell about your first contacts with the Hungarian literature.

─ A Walesi Bardok was my first contact. But since reading that (in translation, of course), I’ve become familiar with more of Arany’s work, and through him also with Petofi. We have in Wales a similar situation: a young and very promising poet, called HEDD WYN (google), was killed in Paschendaele. Another poet, R. Williams Parry, stayed at home because of his health. But the elegy (full of guilt, I say) that R. Wlliams Parry wrote for Hedd Wyn became an elegy for all the young Welshmen lost in that war, and to this day it is well-known and often sung.

─ Arany’s poem, ‘A Walesi Bardok’, is well known in Wales since your translation, what do you think why was necessary 150 years for this?

─ There were translations into Welsh before mine. But the poem never had much of an impact on the Welsh conciousness, because the legend of the burning bards is unknown here.

─ Did you translate from Hungarian or with the help of another language?

─ I was given an absolutely literal English translation in prose of Arany’s poem. But I listened to the original Hungarian on tape in order to hear the rhythm and understand the metre.

─ The massacre in Wales became a symbol, in Arany Janos' poem for aftermaths of the 1848 revolution. There are several translation techniques; how have you translated an idea?

─ All I have done is to translate as closely as possible from the original. There was no jazz freedom to interpret the idea in any new light.

─ ‘Ötszáz bizony dalolva ment lángsírba walesi bárd’. This one single line has a whole literature, do you know, did you follow this literature?

─ ‘Five hundred flames...’ No, I know nothing of that literature. I don’t speak any Hungarian, so I don’t have the key to that door.

2

─ Dr. Heini Gruffudd, you travelled in Central and Eastern Europe, did you travel in Hungary, Transylvania?

─ Every year I take members of me Welsh literature classes to different countries in Europe, for a week. We try to link the visits with aspects of Welsh literature. Some Welsh language authors have lived in Germany and Italy, so we have visited Heidelberg, Worms and Berlin, also Florence and Pisa. In 2013 we are going to Umbria, in Italy.

Because of the poem on the Welsh bards by Arany János, we have visited Budapest in Hungary. We have also visited Poland – Gdansk, Wroclaw and Krakow. We have also been to Prague.

─ How much do you know about the Hungarian culture?

─ Unfortunately not much is known in Wales about Hungarian culture. However, Lajos Kossuth was an inspiration for early Welsh nationalists in the 19th century who wanted Wales to become an independent country. Some of these Welsh thinkers corresponded with Kossuth, and tried to extend his principles to Wales.

We are aware that Hungarian does not belong to the usual Indo-European group of languages, and that Hungary holds a special place in European culture. We are also away of Hungarian minorities in some other European countries.

─ How much do welsh people know about the Hungarian culture?

─ I’m afraid that not much is taught in Wales about Hungarian culture. Some Welsh choirs have visited Hungary. I know that a choir from Morriston, Swansea, where I live, has sung in Hungary. It would be good to expand the knowledge of Welsh people regarding Hungary beyond Rubik!

─ What about the Wales -- Hungarian relationships?

─ Before the establishment of the National Assembly of Wales in 1999, there was little opportunity for Wales to establish contacts as a country with other countries. Although Wales is not an independent country, it now has its own assembly, or parliament, which can pass laws. The Assembly has established contacts with other countries and parts of Europe. The Assembly signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Silesia in 2001, and there have been trade missions to Hungary and other mid European states.

─ The most grandious panorama of the 1848 revolution in Vienna is written by a Hungarian classic, Jókai Mór. His novel was translated more than 2O times, through the German editions well known in the whole world.

Arany János -- A walesi bárdok -- was the poem translated in welsh language?

─ The poem by Arany János has at last become well-known in Wales this year. It has been translated by a Welsh poet – Twm Morys, and music has been composed especially for the poem by one of our most prominent musicians – Karl Jenkins. This was performed this year in our national festival – the National Eisteddfod of Wales. A CD of the music has been produced by CMI records. The first live recording of the Hungarian language poem set to this music was on 29 June 2012 at the Bartok Bela National Concert Hall in Budapest. The first Welsh language performance was then given in August at the National Eisteddfod.

3

─ About the historical event -- what do the Welsh chronicles say? Later -- what are the historists writing?

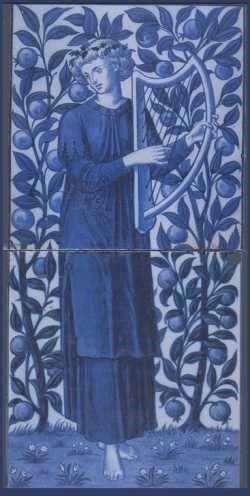

─ I have her a copy of the Chronicle of Welsh Princes, and I’m trying to find it in order to see if anything is there. The symbol of the Welsh bard after the defeat of the Welsh princes is found in pictures in the 18th century, such as this one by Thomas Jones, 1774:

But it is debatable how much history and how much legend is found in the story regarding the killing of 500 poets. It is true that by 1277 Llywelyn II, our last prince, had to agree to harsh terms when Edward I, the English king, led an army of 800 horsemen and 15,000 footsoldiers, into Gwynedd, the part of north Wales which was Llywelyn II’s heartland. Llywelyn II still reigned over parts of Wales, but Edward was buiding a series of castles, surrounded by towns for his army and others. Llywelyn’s final fight for independence was ended when he was killed in 1282.

An English poem, ‘The Bard, 1757, was based on the tradition that the Welsh bards were massacred by Edward I, and the pictures depicting the last Welsh bard are probably based on this. Gray describes the last Welsh bard standing on Snowdon anx cursing the English king Kedwar before throwing himself to the river.

It is, however, doubtful, to what extend this massacre happened.

Here is Thomas Gray’s poem:

"The Bard. A Pindaric Ode"

The following Ode is founded on a Tradition current in Wales,

that EDWARD the First, when he compleated the conquest of

that country, ordered all the Bards, that fell into his hands,

to be put to death.

I. 1.

1 `Ruin seize thee, ruthless king!

2 Confusion on thy banners wait,

3 Though fanned by Conquest's crimson wing

4 They mock the air with idle state.

5 Helm nor hauberk's twisted mail,

6 Nor even thy virtues, tyrant, shall avail

7 To save thy secret soul from nightly fears,

8 From Cambria's curse, from Cambria's tears!'

9 Such were the sounds, that o'er the crested pride

10 Of the first Edward scattered wild dismay,

11 As down the steep of Snowdon's shaggy side

12 He wound with toilsome march his long array.

13 Stout Gloucester stood aghast in speechless trance:

14 `To arms!' cried Mortimer, and couched his quivering lance.

I. 2.

15 On a rock, whose haughty brow

16 Frowns o'er old Conway's foaming flood,

17 Robed in the sable garb of woe,

18 With haggard eyes the poet stood;

19 (Loose his beard, and hoary hair

20 Streamed, like a meteor, to the troubled air)

21 And with a master's hand, and prophet's fire,

22 Struck the deep sorrows of his lyre.

23 `Hark, how each giant-oak, and desert cave,

24 Sighs to the torrent's awful voice beneath!

25 O'er thee, oh king! their hundred arms they wave,

26 Revenge on thee in hoarser murmurs breathe;

27 Vocal no more, since Cambria's fatal day,

28 To high-born Hoel's harp, or soft Llewellyn's lay.

I. 3.

29 `Cold is Cadwallo's tongue,

30 That hushed the stormy main:

31 Brave Urien sleeps upon his craggy bed:

32 Mountains, ye mourn in vain

33 Modred, whose magic song

34 Made huge Plinlimmon bow his cloud-topped head.

35 On dreary Arvon's shore they lie,

36 Smeared with gore, and ghastly pale:

37 Far, far aloof the affrighted ravens sail;

38 The famished eagle screams, and passes by.

39 Dear lost companions of my tuneful art,

40 Dear, as the light that visits these sad eyes,

41 Dear, as the ruddy drops that warm my heart,

42 Ye died amidst your dying country's cries--

43 No more I weep. They do not sleep.

44 On yonder cliffs, a grisly band,

45 I see them sit, they linger yet,

46 Avengers of their native land:

47 With me in dreadful harmony they join,

48 And weave with bloody hands the tissue of thy line.'

II. 1.

49 "Weave the warp, and weave the woof,

50 The winding-sheet of Edward's race.

51 Give ample room, and verge enough

52 The characters of hell to trace.

53 Mark the year and mark the night,

54 When Severn shall re-echo with affright

55 The shrieks of death, through Berkeley's roofs that ring,

56 Shrieks of an agonising king!

57 She-wolf of France, with unrelenting fangs,

58 That tear'st the bowels of thy mangled mate,

59 From thee be born, who o'er thy country hangs

60 The scourge of heaven. What terrors round him wait!

61 Amazement in his van, with Flight combined,

62 And Sorrow's faded form, and Solitude behind.

II. 2.

63 "Mighty victor, mighty lord,

64 Low on his funeral couch he lies!

65 No pitying heart, no eye, afford

66 A tear to grace his obsequies.

67 Is the sable warrior fled?

68 Thy son is gone. He rests among the dead.

69 The swarm that in thy noon-tide beam were born?

70 Gone to salute the rising morn.

71 Fair laughs the morn, and soft the zephyr blows,

72 While proudly riding o'er the azure realm

73 In gallant trim the gilded vessel goes;

74 Youth on the prow, and Pleasure at the helm;

75 Regardless of the sweeping whirlwind's sway,

76 That, hushed in grim repose, expects his evening-prey.

II. 3.

77 "Fill high the sparkling bowl,

78 The rich repast prepare,

79 Reft of a crown, he yet may share the feast:

80 Close by the regal chair

81 Fell Thirst and Famine scowl

82 A baleful smile upon their baffled guest.

83 Heard ye the din of battle bray,

84 Lance to lance, and horse to horse?

85 Long years of havoc urge their destined course,

86 And through the kindred squadrons mow their way.

87 Ye towers of Julius, London's lasting shame,

88 With many a foul and midnight murther fed,

89 Revere his consort's faith, his father's fame,

90 And spare the meek usurper's holy head.

91 Above, below, the rose of snow,

92 Twined with her blushing foe, we spread:

93 The bristled Boar in infant-gore

94 Wallows beneath the thorny shade.

95 Now, brothers, bending o'er the accursed loom,

96 Stamp we our vengeance deep, and ratify his doom.

III. 1.

97 "Edward, lo! to sudden fate

98 (Weave we the woof. The thread is spun)

99 Half of thy heart we consecrate.

100 (The web is wove. The work is done.)"

101 `Stay, oh stay! nor thus forlorn

102 Leave me unblessed, unpitied, here to mourn:

103 In yon bright track, that fires the western skies,

104 They melt, they vanish from my eyes.

105 But oh! what solemn scenes on Snowdon's height

106 Descending slow their glittering skirts unroll?

107 Visions of glory, spare my aching sight,

108 Ye unborn ages, crowd not on my soul!

109 No more our long-lost Arthur we bewail.

110 All-hail, ye genuine kings, Britannia's issue, hail!

III. 2.

111 `Girt with many a baron bold

112 Sublime their starry fronts they rear;

113 And gorgeous dames, and statesmen old

114 In bearded majesty, appear.

115 In the midst a form divine!

116 Her eye proclaims her of the Briton-line;

117 Her lion-port, her awe-commanding face,

118 Attempered sweet to virgin-grace.

119 What strings symphonious tremble in the air,

120 What strains of vocal transport round her play!

121 Hear from the grave, great Taliessin, hear;

122 They breathe a soul to animate thy clay.

123 Bright Rapture calls, and soaring, as she sings,

124 Waves in the eye of heaven her many-coloured wings.

III. 3.

125 `The verse adorn again

126 Fierce war and faithful love,

127 And truth severe, by fairy fiction dressed.

128 In buskined measures move

129 Pale Grief, and pleasing Pain,

130 With Horror, tyrant of the throbbing breast.

131 A voice, as of the cherub-choir,

132 Gales from blooming Eden bear;

133 And distant warblings lessen on my ear,

134 That lost in long futurity expire.

135 Fond impious man, think'st thou, yon sanguine cloud,

136 Raised by thy breath, has quenched the orb of day?

137 Tomorrow he repairs the golden flood,

138 And warms the nations with redoubled ray.

139 Enough for me: with joy I see

140 The different doom our fates assign.

141 Be thine despair and sceptered care;

142 To triumph, and to die, are mine.'

143 He spoke, and headlong from the mountain's height

144 Deep in the roaring tide he plunged to endless night.

─ The historical event is living and re- and reborning through the centuries…

─ A book by the landowner, Sir John Wynn o Wydir, entitled History of the Gwydir Family, written around 1580, notes the lack of poems written to his family in a time when such poems were common:

“This (a poem by Rhys Goch Eryri) is the most ancient song that I can find extant to any of my ancestors since the reign of Edward the First who caused our bards all to be hanged by martial law as stirrers of the people to sedition; whose example, being followed by the governors of Wales, until Henry the Fourth's time was the utter destruction of that sort of man.”

(This quotation comes from: Syr John Wynn, History of the Gwydir Family and Memoirs, ed. J. Gwynfor Jones (Gwasg Gomer, 1990), page. 24.)

─ Do we know other authentic sources?

─ There is no evidence in other Welsh sources for this.

─ Later – what are the historists writing?

─ Sir John Wynn’s story appeared again in History of England (1747-55) by an English historian, Thomas Carte.

─ Please, talk about the presence of this tragedy in your art and literature, respectively in the art and literature of the world.

─ The poet Thomas Gray used this story in his poem The bard, written in 1757. He wrote the poem after hearing the Welsh harpist, Edward Jones, play Welsh melodies on the harp.

─ And in the art?

─ Many artists were inspired to paint a picture of the story. These artists includ Paul Sandby, the Welshman Thomas Jones, and the most well-known painting is by John Martin (1789-1854).

The Bard (ca. 1817), by John Martin

─ The story is living not only in Wales…

─ The story became well-known in many countries, and Janos Arany wrote his popular poem in 1857.

4

─ Did you find parallels in the Wales -- Hungarian history?

─ It is clear that both countries have suffered under foreign domination. Wales was conquered in the 13th century, but has managed to survive as a country until today, although only 20% speak the Welsh language. Poets have always held a place of honour in Wales. The main prizes in our national festival are for poets. This tradition goes back to 1176, when the first recorded ‘Eisteddfod’ was held.

Lajos Kossuth was admired in by the early Welsh nationalists of the modern era, in the 19th centuryand there was correspondence between them.

─ What was your motivation, why did you begin to analize Arany s poem, a masterpiece of a far culture?

─ Twm Morys wrote the translation, and in the television programme he says that he tried to keep to the rhythm and meter of the original, but included some techniques of Welsh poetry.

─ How did the work go off?

─ I was present when the work was first presented in Wales, in the National Eisteddfod in the Vale of Glamorgan in 2012. The music by Karl Jenkins was dramatic, and the event clearly linked Welsh and Hungarian culture.

─ The presentation in Budapest at the Bartók Béla Fesztivál was a great success. There was present Charles, prince of Wales. How could you evaluate in brief the reception in Wales, in the UK?

─ The poem, set to music, was very well received in Wales. The Hungarian poem has been a mirror for us to view our own history, and to reflect on the way in which our country was conquered. The story may not be true, but it has been recorded in English, in a book on English history, and by the poet Thomas Grey. The myth is better than the history, possibly.

─ You travelled in many countries, met many cultures, you speak many languages, did you meet other cultures, literatures, where an event of the Welsh history is so important? Being in the same historical situation, in the Hungarian culture since 15O years grew up many generations thinking on Wales bravery with the greatest respect, with greatest friendship. Did you meet other strong parallels?

─ I speak Welsh, German and English. The story of the king Arthur, a Welsh king, is renowned throughout Europe, although many do not know that he was a Welsh king who fought the Saxon invaders. Once again, more myths than history are associated with him.

The poem by Arany is very different in that it specifically praises the Welsh for the way they resisted the English king.

─ As I know, today's poets of the Eistedfodd Festival are called bards -- but only for the time of the Festival. Do bards exist today? Who are their successors?

─ The Welsh for ‘poet’ is ‘bardd’. So the word ‘bardd’ is always used for Welsh poets. In English the word ‘poet’ is generally used, and ‘bard’ is more or less kept for the National Eisteddfod Festival.

The National Eisteddfod was re-established in the mid 19th century, and every year two prizes are won by the bards: a crown and a chair.

─ To be a poet, a Bard in Wales -- what it does mean today?

─ Wales has many poets, or bards. There are two winners in the Eisteddfod every year, and a poet is not allowed to win more than three times. So there are alive probably around 100 – 150 winners of these prizes – all bards of the Eisteddfod. The Eisteddfod Ceremony is run by an Associaton of Bards – Gorsedd y Beirdd.

Poetic competitions are very popular. There is usually a weekly competition between teams of poets. This is called ‘Talwrn y Beirdd’ - ‘Cockpit of the Bards’.

─ What are you working on now?

I am working on books for learners of Welsh.

─ What are your plans?

─ I will always try my best to secure a future for the Welsh language. I am involved in a Welsh Centre (Tŷ Tawe) in Swansea, and also a new movement – ‘Dyfodol i’r Iaith’ (A future for the Welsh Language)

─ The story became well-known in many countries, and Janos Arany wrote his popular poem in 1857.

4

─ Did you find parallels in the Wales -- Hungarian history?

─ It is clear that both countries have suffered under foreign domination. Wales was conquered in the 13th century, but has managed to survive as a country until today, although only 20% speak the Welsh language. Poets have always held a place of honour in Wales. The main prizes in our national festival are for poets. This tradition goes back to 1176, when the first recorded ‘Eisteddfod’ was held.

Lajos Kossuth was admired in by the early Welsh nationalists of the modern era, in the 19th centuryand there was correspondence between them.

─ What was your motivation, why did you begin to analize Arany s poem, a masterpiece of a far culture?

─ Twm Morys wrote the translation, and in the television programme he says that he tried to keep to the rhythm and meter of the original, but included some techniques of Welsh poetry.

─ How did the work go off?

─ I was present when the work was first presented in Wales, in the National Eisteddfod in the Vale of Glamorgan in 2012. The music by Karl Jenkins was dramatic, and the event clearly linked Welsh and Hungarian culture.

─ The presentation in Budapest at the Bartók Béla Fesztivál was a great success. There was present Charles, prince of Wales. How could you evaluate in brief the reception in Wales, in the UK?

─ The poem, set to music, was very well received in Wales. The Hungarian poem has been a mirror for us to view our own history, and to reflect on the way in which our country was conquered. The story may not be true, but it has been recorded in English, in a book on English history, and by the poet Thomas Grey. The myth is better than the history, possibly.

─ You travelled in many countries, met many cultures, you speak many languages, did you meet other cultures, literatures, where an event of the Welsh history is so important? Being in the same historical situation, in the Hungarian culture since 15O years grew up many generations thinking on Wales bravery with the greatest respect, with greatest friendship. Did you meet other strong parallels?

─ I speak Welsh, German and English. The story of the king Arthur, a Welsh king, is renowned throughout Europe, although many do not know that he was a Welsh king who fought the Saxon invaders. Once again, more myths than history are associated with him.

The poem by Arany is very different in that it specifically praises the Welsh for the way they resisted the English king.

─ As I know, today's poets of the Eistedfodd Festival are called bards -- but only for the time of the Festival. Do bards exist today? Who are their successors?

─ The Welsh for ‘poet’ is ‘bardd’. So the word ‘bardd’ is always used for Welsh poets. In English the word ‘poet’ is generally used, and ‘bard’ is more or less kept for the National Eisteddfod Festival.

The National Eisteddfod was re-established in the mid 19th century, and every year two prizes are won by the bards: a crown and a chair.

─ To be a poet, a Bard in Wales -- what it does mean today?

─ Wales has many poets, or bards. There are two winners in the Eisteddfod every year, and a poet is not allowed to win more than three times. So there are alive probably around 100 – 150 winners of these prizes – all bards of the Eisteddfod. The Eisteddfod Ceremony is run by an Associaton of Bards – Gorsedd y Beirdd.

Poetic competitions are very popular. There is usually a weekly competition between teams of poets. This is called ‘Talwrn y Beirdd’ - ‘Cockpit of the Bards’.

─ What are you working on now?

I am working on books for learners of Welsh.

─ What are your plans?

─ I will always try my best to secure a future for the Welsh language. I am involved in a Welsh Centre (Tŷ Tawe) in Swansea, and also a new movement – ‘Dyfodol i’r Iaith’ (A future for the Welsh Language)